|

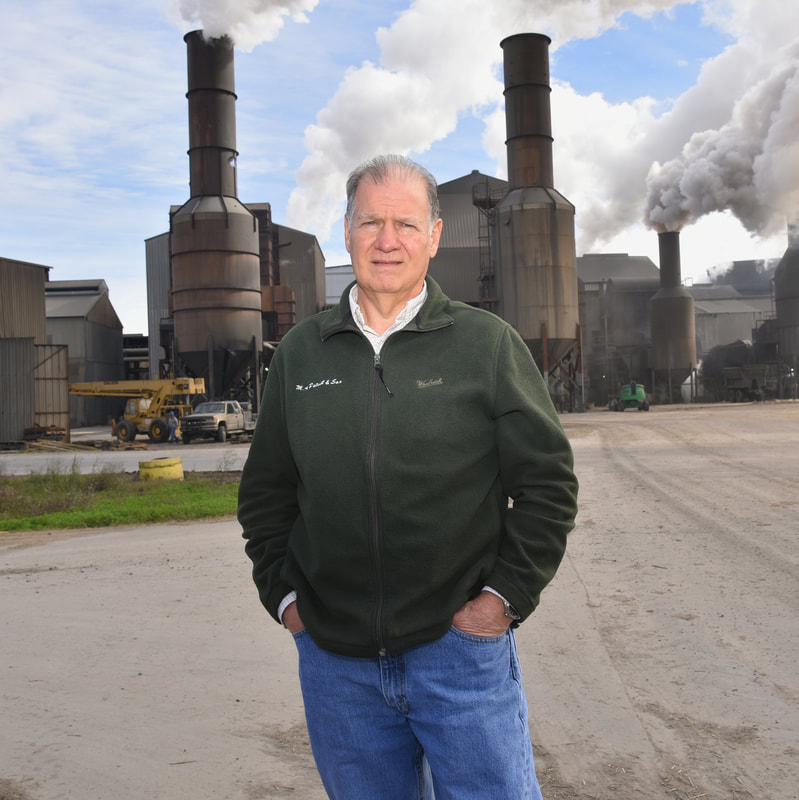

Story and photos by Bruce Schultz JEANERETTE – This year’s cane crop for the Patout sugar mill, the Enterprise Factory, between Jeanerette and New Iberia has not been stellar, thanks to the weather.

Randy Romero, M.A. Patout and Sons chief executive officer, said the yield of roughly 30-32 tons per acre, was less than his expectation of 35-40 tons. Patout processed 2.55 million tons of cane last year, but this year’s total will be about 2.1 million, Romero said. Grinding started Sept. 24 at the Enterprise Mill and ended on Dec. 30. Sugar recovery was better than last year, he said, about 208 pounds per ton, compared to 202 pounds of the 2018 crop. Romero said several factors contributed to the lower yields. “Last year was extremely wet.” And that miserable wet harvest of 2018-19 didn’t help this year’s, causing damage to stubble, he said. Disease, specifically rust, was a problem in 2019 that probably resulted from the mild winter of 2018-19. Fertilizer probably lost some of its effectiveness because it was applied in wet conditions in the spring, he said. “We never really saw good growth.” Then along came Hurricane Barry in July at a crucial growth stage. Plants probably lost about 3-4 weeks of growth, Romero said. “It shredded the leaves and leaned the cane in some areas. It put that cane in shock.” The fields were wet through August, but dried for planting in September, he said. “Overall, our harvest season went fairly well.” Romero said the 2018-19 crop had higher tonnage because of a late growth spurt in September and October 2018, but that didn’t happen this year. “It wasn’t significant enough to contribute to a high tonnage year.” The freeze in this past November caused the sucrose level to decrease, but Romero said the effect was somewhat minimized because of the cold tolerance of varieties 299 and 540. “Outside of the freeze, we’ve had fairly good harvest weather.” Dr. Kenneth Gravois, LSU AgCenter sugarcane specialist, agreed with Romero’s conclusion about the muddy harvest a year ago affecting the most recent crop. “It was a light crop. Anytime you have a muddy harvest, in the previous year, you have a hangover effect into the next year.” He said the average yield was 30.2 tons per acre statewide, compared to 39.3 tons the previous year. “That was a record tonnage last year.” But he said the average sugar extraction of 222 pounds of sugar per ton of cane was an improvement over last year when the average was 219 pounds. Gravois said this crop was about average, and for the most part harvest conditions were dry, and planting was accomplished in good conditions. “We’re going to be optimistic for next year.” Gravois said the recent cane acreage totaled 482,300, compared to 459,000 in 2018. He expects acreage to increase for 2020, possibly as much as 490,000 acres, as more land is put into cane production to the west and north. Blair Hebert, LSU AgCenter county agent for sugarcane in the Bayou Teche area, said fields were badly damaged in 2018 during the muddy harvest. He said Hurricane Barry damaged the cane worse than was initially thought with the tops of cane plants broken. The early freeze put a freeze on sugar production in the plants, he said. “This is one of those tough years that Mother Nature didn’t give us much to work with,” Hebert said. “Overall, this is not going to go down as a good yielding year.” Romero said Louisiana mills must run at a high-volume capacity to be profitable. To make sure that happens the Patout Equipment Corp. (PEC), formed in 2005, with a fleet of 42 combines and 220 trucks, harvests and hauls about two-thirds of the cane processed by the Patout mills. Contract haulers were used to bring much of the cane to the mills, but high insurance costs drove them out of business, which led to the formation of harvest groups like PEC. Foreign labor through the H2A program makes up most of the harvest company’s workforce, Romero said. “Our industry would be in serious trouble without it.” He said it’s impossible to find enough licensed commercial drivers in the U.S. to staff the seasonal labor demand. “Our industry can’t go back.” It’s becoming more difficult to get seasonal workers into the country in time for the harvest of Louisiana’s $3 billion crop, he said. Immigration laws need refined to better define farm labor and farm activities, he said. “All 11 mills in Louisiana struggle with labor,” Romero said. Cane is sprayed with ripener 35 days before harvest, and everything is ready but everything rests on getting workers into the country in time to start cutting cane. Also federal labor laws don’t classify the mill factory workers as agricultural and that also slows down the process of getting the labor here on time. “It should all be part of agricultural activity.” Romero said Patout has expanded to the west, contracting with farmers in Vermilion Parish, and to the north in Acadia Parish and up to Cheneyville because available cane land has become scarce in St. Martin, Lafayette and Iberia parishes because of development. And those new residents living in those new subdivisions are not as accepting of traditional farm practices, like burning cane leaves. With the longer harvests, all Louisiana farmers are concerned with freezing weather, but they have the option of buying crop insurance to protect their investment, Romero said. “Although it can be expensive, we encourage our farmers north of I-10 to buy crop insurance.” Romero is convinced that tort reform in Louisiana would result in lower insurance premiums for cane trucks over time. The American Sugar Cane League and other pro-business organizations are working on that, he said. “We need tort reform in Louisiana desperately.” He said PEC does its part towards safety in the field and on the road, with GPS monitors, dash video cameras in the trucks and radio communications. “We’ve got a stringent safety and enforcement plan.” County Agent Hebert said the company’s safety program demonstrates that Patout is a leader at making a proactive approach to potential problems. “They have come up with concepts and ideas to address issues that arose. And they are very supportive of the farmers.” The Sterling mill added a four-roller mill unit in 2019 to increase capacity and the Enterprise and Raceland mills will have new similar units online for the 2020 harvest to increase daily capacity, Romero said. The Enterprise mill has 250 employees for grinding, and 180 during the off-season. The Patout operation includes the Enterprise mill between Jeanerette and New Iberia, the Sterling Sugar Mill in Franklin and a raw sugar mill in Raceland. Patout is a privately held corporation, not a cooperative among farmers. Romero grew up in Youngsville, graduated from the University of Southwestern Louisiana in 1981, and became a CPA working for an Abbeville accounting firm. In 1989, he went to work for the Sterling mill and in 2002 became the chief financial officer for Patout after it bought the Sterling mill. In 2014, he was chosen as the chief executive officer for Patout. Romero said the start and end of grinding season is stressful on everyone. “The Patout organization is made up of a great group of dedicated people from its Board of Directors, officers, managers, supervisors, and all its employees and farmers, all of equal value,” Romero said. “Today, as in the past, the Louisiana sugar industry is blessed to have great people.”

1 Comment

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed